Brown bear

100 years of slow bear conservation progress in Sweden is right now being undone at an alarming speed. Mainly, because of high trophy hunting quotas permitted by the Swedish government. This is not compatible with the bear’s status as a Protected species, neither in Sweden nor in the EU.

Why now?

Against EU law (EU’s Habitat Directive), the licensed quota hunt killed around 25% of Sweden’s bear population in 2023. This to satisfy certain special-interest groups and officially said to be a way to “increase acceptance”. In 2023 a total of 722 bears were killed “legally” in Sweden. Government policies now seem to aim to bring down Sweden’s bear population as close as possible to the defined “Favorable reference population” level. Which would mean about 1,400 bears, compared to the official estimate of 2,450 in 2023. That would mean losing more than 50% of Sweden’s bears compared to the official estimated number of 3,300 bears in 2008.

According to 2023 official statistics, 648 bears were killed during “licensed quota hunting” and a further 74 bears killed during so-called “protective hunting”. Hunting is, since long, the main limiting factor for Sweden’s bear population. Poaching is a problem and a crime, but it is the extensive “licensed quota hunting” that is the most problematic for the bears. Especially when combined with generous permits for “protective hunting”. Quotas are officially justified by the authorities as a method to actively reduce the number of bears.

According to EU law (EU Habitats Directive), the bear is Strictly protected, and population-depressing (or quota) hunting is not compatible with the Directive. Still, this is precisely what is happening in Sweden right now. Special interest groups are trying to push up hunting quotas for all large carnivores, including the bear, leading to their numbers being pushed down to soon critically low levels. Sweden’s policy is shifting towards the minimum “Favorable reference population” level (to maintain Favourable conservation status), now being promoted to be seen as the new maximum population levels (determined by politicians and hunters “to increase acceptance”).

Bear conservation

The decline from 3,300 bears in 2008 to officially 2,450 in 2023, is mainly due to “legal quotas”, allowing the killing of many hundreds of bears. Licensed hunting, to a great extent means “trophy hunting” and attracts a large number of hunters, also foreign hunters.

The bear has historically lived throughout most of Sweden, but was exterminated from southern Sweden in the 1800’s. It survived further north, and was down to only some 130 individuals by 1927, when it was finally protected by law. This saved the bear from total extinction and bear numbers began to rise again, however slowly, mainly due to frequent poaching.

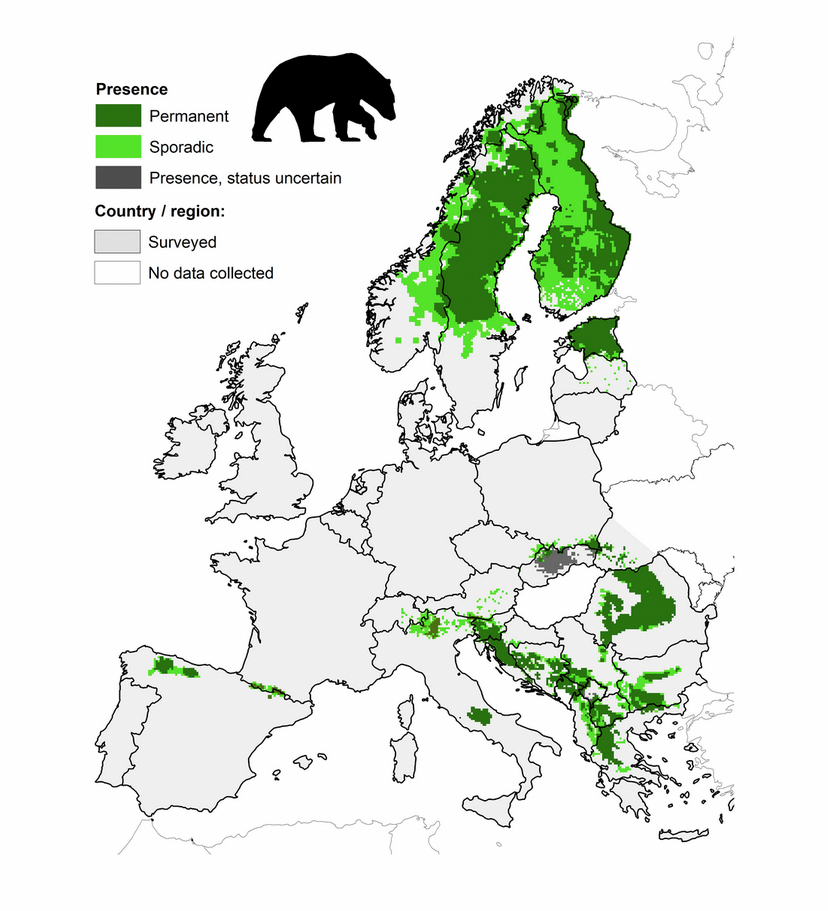

The bear is included in the Bern Convention and classified as “Near Threatened (NT)” in the Swedish Red List (2020), published by the Swedish Species Information Centre (SLU Artdatabanken) at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. The total number of bears in Europe was in 2022 estimated to between 14,000 and 22,000. Sweden has about 10% of them.

Why does the ecosystem need the bear?

The bear is a vital part of our ecosystems since the Ice age. As a top predator it influences the numbers, population size and behavior of its’ prey species. Bears are omnivores, meaning they eat almost anything. In Sweden bears most of all eat large amounts of ants, vegetation and berries, where they spread seeds far and wide, planted through their rear end with excellent fertilizer around. Bears also predate on moose and reindeer, especially on their calves during summer, and thereby influence these animals’ grazing and browsing pressure. Bears also feed on carrion, acting as one part of the clean-up squad in nature, limiting the spread of disease. They also influence the ecosystem where they live by taking down trees, digging in the ground and opening up anthills, thereby helping plants, insects, fungi, smaller mammals and a number of bird species.

Why are bears hunted in Sweden?

Basically, it comes down to competition between humans and the other carnivores. There are two official ways to hunt bears: Protective hunting “to protect property”, and licensed quota hunting.

Licensed hunting of bears (648 bears in 2023) is mainly done to “increase acceptance” and control its population size. This quota hunting, approved by the Swedish state, is the most serious threat to the bear population. The setting of such quotas is heavily influenced by hunting interests, with little say from anyone else. The justification for it has a very weak scientific evidence base.

Protective hunting (74 bears in 2023) is officially allowed when bears might kill domestic livestock, mostly reindeer, but sometimes also sheep and the odd cow or horse. In 2022, 10 out of Sweden’s 342,000 sheep were killed by bears, and 1 out of 296,500 cows. As an animal owner, you have certain legal rights to kill a predator that attacks your animals. Farms in bear areas are recommended to prevent predator attacks mainly by putting up predator-proof electric fences or using guard dogs. Livestock losses are more likely to happen in farms that have not yet taken preventive countermeasures, such as putting up predator-proof electric fencing. Once such fences are up and running, the risk of predation from all predator species (including the neighbour’s dogs) usually decreases dramatically. At a national scale, sheep losses caused by bears is a very small problem.

Protective hunting rights can be expanded into preventive measures, which is most common in the reindeer herding areas in the North, where bears can cause sizeable economic damage to reindeer stock. According to estimates by the Sami Council (Sametinget) in 2024, bears kill between 3,500-7,500 reindeer per year, out of the 250,000 reindeer in the country. At a national scale, predation on reindeer is the only sizeable problem caused by bears in Sweden, costing the state about 180,000 euro per year in damage compensation payments, plus the losses for the community of herdsmen.

Are bears dangerous to people?

Bears are large and powerful, but also very shy animals. They generally avoid human contact. Over the last 100 years only two people have been killed in bear accidents in Sweden (2004 and 2007), both in connection with hunting and gun dogs. The relatively few documented bear accidents in all of Europe are caused almost exclusively by bears feeling threatened in one of the following three situations:

- A bear is wounded or chased by gun dogs during hunting (the most common).

- A person, or a dog, comes too close to a bear mother’s young cubs.

- A person, or a dog, comes too close to the bear’s prey.

A key trigger for aggression seems to be surprise. Apart from the specific situations above, bears generally can be regarded as unaggressive. If you, against all odds see a bear in the forest, then let it know that you are there. Talk slowly to it, stop and don’t approach. Avoid direct eye-contact. Instead, turn your side to it, slowly move away and continue talking, like you would do if you meet a big dog you don’t know. If you happen to come across bear cubs, immediately leave the area the same direction that you came from. Bear cubs are almost never abandoned. A bear will stand on its hind legs to get better overview, so this is not an aggressive behaviour. Bears have right of way.

Bear facts

Latin: Ursus arctos (Linnaeus 1758)

Swedish: Björn

The bear is a large mammal with a colour that varies from very blond to almost black. It has a very sharp sense of hearing, a phenomenal sense of smell, but an eyesight that probably is poorer than the human’s. Bears are very adaptable and can live almost anywhere, as long as there is food and they are not killed. A favourite bear menu stretches from ants, nuts and berries, over carrion and moose, to honey and garbage. In Sweden, most bears live north of a line from Värmland to northern Uppland.

During the mating season males cover huge distances in search of females to mate with. During winter, 1-4 cubs are born, the size of small guinea pigs, in their den. In April or May, they leave the den and follow their mother for up to two years.

Bears hibernate in winter, for almost half a year, losing up to half their body weight. During hibernation, bears neither eat nor drink, surviving on their body fat, built up by the abundance of food during summer. The den can be in a hole in the ground, in an old anthill, or under an uprooted tree or a dense spruce. The bear has a wide repertoire of sounds, from a cow-like mooing, over whistling sounds, to full-on roars.

Swedish Carnivore Association’s comments

- There is room for many more bears in Sweden than today and there should be no quota hunting of bears, nor of any other strictly protected predators.

- Carnivore policies should first of all promote co-existence, to learn how to live side by side. This is also basic EU policy.

- We believe protective hunting is acceptable, provided that other possible solutions are tried, such as predator-proof fencing and/or moving domestic animals indoors at night.

- There should be long-term viable populations of all original predator species in Sweden, in their native distribution area.

Image credits

From the top: 1 Staffan Widstrand, 2 Magnus Lundgren, 3-6 Staffan Widstrand

Map: Kaczensky, Petra et al. (2021). Distribution of large carnivores in Europe 2012 – 2016

Links

- 648 bears killed in Sweden in licensed hunting 2023 (SRF, 2023, Swedish)

- An attitude survey about large carnivores and wildlife management in Sweden (Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SLU, 2021, Swedish)

- Keeping predators out - fences to reduce livestock depredation (Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SLU, 2020, English)

- Domestic animal losses and other damage by wildlife 2022 (Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SLU Viltskadecenter, 2023 Swedish)

- Distribution maps for Brown bear, Eurasian lynx, Grey wolf, and Wolverine [Dataset]. Kaczensky, Petra et al. (2021). Distribution of large carnivores in Europe 2012 - 2016: Dryad

News

Hundreds of millions wasted on culling wolf population

- 8 October 2025

Podcast well worth listening to

- 19 September 2025

250,000 Swedish kronor reward for tips on illegal hunting of large predators

- 10 September 2025

124 swedish bears shot on the first day of hunting

- 21 August 2025

Sweden prepares for another major bear hunt

- 4 August 2025

EU Court ruling confirm flaws in Sweden’s wolf policy

- 11 July 2025