Wolf

Right now, wolf numbers in Sweden are being pushed down at an alarming rate. Mainly because of high trophy hunting quotas, permitted by the Swedish authorities. The official number of wolves is also very easy to misunderstand, since it counts many dozens of dead wolves as being alive, including all individuals killed during the licensed hunt each year.

Why now?

50 years of slow come-back progress of the wolf in Sweden is presently being undone at an alarming speed, mainly because of the unproportionally high influence from narrow, special interest groups on the decision-making process.

70 wolves were “legally” killed in Sweden in 2023, representing about 15% of its wolf population. In January 2024, a further 35 wolves were killed during the licenced hunting. Government policy now seems to be to try to force down the wolf population to the bare minimum legally possible level, called “Favorable reference population” (FRP), which then will mean a Swedish wolf population of as few as 300 wolves. The clear ambition from the government is to also try to lower that FRP number even further, preferably to 170 wolves. This for political reasons, to satisfy narrow, special-interest groups, but against EU law and against the outspoken recommendations from a number of scientists.

There are also statistic riddles and smokescreens in play regarding when in the calendar year wolf numbers are counted and how these numbers are presented. The reporting of wolf numbers is not done when the population is at its lowest. Thereby the official number of wolves also include all known dead wolves during the survey period. If official wolf numbers easily give the impression that there are many more wolves than there actually are at the lowest point in the year, hunting quotas risk becoming too high as well.

Are the numbers correct? In the winter 2022/2023, there were officially an estimated 450 wolves in Sweden. Counted by taking the number of confirmed family group territories multiplied by 10 (several scientists prefer using a factor 8, meaning an estimated 360 wolves) instead. That official number, whether 450 or 360, still hides another statistical smokescreen: the number of wolves killed during licensed hunting (57) and protective hunting (13) in 2023, are not deducted from the official number, nor are any other wolves knowingly killed – by poaching, road traffic or natural causes during the survey period.

The official number 450 is then used by the government and the special interest groups that they are supporting, to argue for higher hunting quotas the following year, but the number is full of already dead wolves. A more realistic wolf number at its lowest point in 2023 would have been around 300. Which happens to be the minimum “Favorable reference population” level, to keep “EU Favorable Conservation Status”. Fresh official numbers for the winter 2023/2024 now report 375 wolves. Which again does not deduct the 35 killed during the 2024 licensed hunt, nor the so far unknown number killed in protective hunting, poaching and traffic during the survey period. A more realistic wolf number at its lowest point of 2024 is well below 300, possibly even around 250.

Hunting is, since long, the main limiting factor for Sweden’s wolf population. Illegal hunting (poaching) of wolves is a very serious problem and a crime. But the “licensed quota hunting” in combination with the generous “protective hunting”, is maybe even more problematic for the wolf population. It is justified by the authorities to actively reduce the number of wolves, in order to “increase acceptance”. However, recent studies (by Dressel) indicate that such “acceptance” cannot be seen yet, in spite of 14 years of licensed wolfhunting.

According to the EU Habitats Directive, which is law, the wolf is Strictly protected, and population-depressing, or quota hunting is not compatible with the directive. Still, precisely this is being carried out in Sweden.

Wolf conservation

Wolves have historically lived throughout Sweden, except on the island of Gotland. Hundreds of geographical names include the word wolf (varg or ulv) or noa names for it. By 1870 the wolf was exterminated from southern Sweden, and in the early 1900s the wolf was only found in the North. Bounties were paid for killed wolves until 1965, when the species instead became protected. By then, it was in practice extinct in Sweden and Norway. However, in 1983, a wolf litter was born in northern Värmland, with two Fenno-Russian immigrant wolves as parents. This family was the start of the present-day wolf population in Scandinavia.

Wolf numbers in Sweden are up from zero (1966-1982), but down from the recent peak of an estimated 460 wolves in 2021. Current decrease is due to hunting, licensed and protective, as well as poaching in some regions. Licensed hunting to a great extent means “trophy hunting” which also attracts numbers of foreign hunters.

The wolf is protected by the Bern Convention, and classified as “Endangered, (EN)” in the Swedish Red List, published by Swedish Species Information Centre (SLU Artdatabanken) at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

Why does the ecosystem need the wolf?

The wolf is a vital part of our ecosystems since the Ice age. As a top predator it influences the numbers, population density and behavior of its’ prey species. Most wolf families primarily feed on moose and roe deer, thereby locally limiting their grazing and browsing pressure and distribution. The wolf picks its prey by chosing carefully, often the least viable and most easy-to-catch individuals of each species. This in clear contrast to the human hunter, who very often choses to kill the strongest and most beautiful individuals. Moose, reindeer, wild boar, beaver and red deer actually look and behave the way they do, because of hundreds of thousands of years of co-evolution with the wolf, keeping the species’ genetics healthy. Leftovers from wolf meals provide important food for birds, mammals, insects, fungi and plants. Wolves kill smaller predators, thereby limiting some of the predation pressure on their prey species, such as grouse, capercaillie, hare or roe deer.

Wolves feed on carrion as well, acting as one part of the clean-up squad in nature, limiting the spread of disease. Swine flu outbreaks among wild boar has been found to be limited by wolves. No studies have yet been made in Sweden about wildlife road collision statistics, correlated to predator densities. Research in North America however indicates that changes in prey behavior and numbers seems to lead to large predators actually helping to make roadways safer.

Why are wolves hunted in Sweden?

Basically, it comes down to competition between humans and other large carnivores. There are two official ways to hunt wolf: protective hunting “to protect property”, and licensed quota hunting, “to increase acceptance” and bring down wolf numbers.

Protective hunting is officially allowed when wolves might kill domestic livestock, mainly sheep and reindeer. 251 out of Sweden’s 342,000 sheep were killed or wounded by wolves in 2022. Farms in wolf areas are recommended to try to prevent predator attacks, mainly by putting up predator-proof electric fences and using guard dogs. Livestock losses are much less likely in farms that have taken preventive countermeasures. Electric fencing almost eliminates the problems with wolf predation on farm livestock. It also keeps other large predators out, including the neighbour’s dogs. At a national scale, sheep losses caused by wolf is a small problem, but for the individual owner, it can of course be a serious loss. Every single sheep killed by a wolf tends to make the headlines.

In the reindeer herding areas in the north, wolves today cause very little economic damage to reindeer husbandry. This because wolves tend to be shot there on sight. According to estimates by the Sami Council (Sametinget) in 2024, wolves kill between 70 to 150 reindeer per year, out of 250,000 reindeer in the country. At a national scale, wolf predation on reindeer is of limited cost to the involved parties. However, without protective hunting of just about every wolf entering into reindeer land, those numbers would have been substantial.

Licensed hunting of wolf is mainly done to “increase acceptance” and to reduce its population size. A wolf hunting quota is set each year, where every step in the decision making process is heavily influenced by hunting interests. In reality, this quota hunting is carried out because of two reasons. First, because the wolf is seen as the worst competitor of all, for prey that hunters give themselves the right to kill first. Hunters’ right to kill always supersede other carnivores’ right to do so. Second, because of a certain demand for trophy and pleasure hunting. Neither of these two reasons should motivate a legal trophy hunt of a Strictly protected animal. The Swedish authorities that issue hunting quotas (based on the Government’s intentions) have therefore been taken to court several times in Sweden. There is an ongoing formal complaint lodged with the EU Commission, about the Swedish wolf hunt, and since March 15, 2024, also a formal complaint lodged about the Swedish lynx hunt, both filed by the Swedish Carnivore Association.

Another reason for wolf hatred is that wolves can kill gun dogs that venture into wolf territory, which is not appreciated by the dogs’ owners. 22 dogs were wounded or killed by wolves in 2020 in Sweden. Compared to 400 dogs killed by wild boar (re-introduced by hunters), 129 in road traffic accidents, 17 drowned and 5 that were shot dead by accident, the same year. Poaching has always been a serious threat to the wolf in Sweden. However, the “licensed quota hunting”, nowadays approved by the Swedish state, seems to be a possibly worse threat to the wolf population. Since 2010, licensed hunting of wolf has been allowed, which in practice has developed into an annual population-regulating hunt. The setting of licensed hunting quotas is heavily influenced by hunting interests, together with the Federation of Swedish Farmers (LRF), but with very little say from anyone else.

Are wolves dangerous to people?

Wolves are usually extremely shy and it is safe to say that wolves avoid humans as much as possible, and they are not interested in humans as prey. The only properly documented case in Sweden of a lethal wolf attack on a human was in 1821, and this incident involved a wolf raised in captivity, but later as an adult stupidly released into the wild. The wolf is unsuitable as a pet.

There have been amazingly few properly documented lethal wolf attacks in Europe through the centuries. Mainly some cases during extreme circumstances, such as large wars when people kill people by the millions, and rabies epidemics. Five people are said to have been killed by non-rabies-infected, wild wolves in Europe outside over the last 75 years Russia (all in Spain, during the Franco dictatorship). A further five are described to have died after being bitten by wolves infected by rabies (in Latvia, Estonia and Slovakia, during Soviet dictatorship). These data are today seen as possibly questionable.

Domestic dogs tend to in reality be far more dangerous to humans than wolves are. The number of EU citizens killed by dogs from 1995 to 2016 was estimated at 827, according to Forensic Science International/Eurostat.

Wolf facts

Latin: Canis lupus (Linnaeus 1758)

Swedish: Varg

The wolf is the largest of the 35 living wild species in the dog family, Canidae. Every race of domestic dog in the world has come from the wolf. Scandinavian wolves are basically grey, reddish and beige, with darker areas that come from black tips of some hairs. They often have black markings on their legs, in the face, on the back and almost always a large black spot at the base of the tail. The summer coat is more reddish brown and the ears are often very reddish buff. The chin/throat is always white.

The wolf is very adaptable and can live almost anywhere, as long as there is prey and not too heavy persecution. It has a wider distribution across the northern hemisphere than any other large carnivore, except for the Human. In a great variety of habitats, from deserts to mountains, forests, grazing lands and tundra.

Wolves live in family groups, with a female, a male and their latest litter. One or two pups of the previous litter often remain with the family for an extra year. The female gives birth in April-May to usually 2-6 pups, in a den in a burrow or in a dry place, hidden by thick bush. Wolf families are strictly hierarchical. Highest rank belongs to the father and mother, often called the “Alpha couple”. They are strongly territorial, with territories of up to 1,000 square kilometers in size, defended against any incursions of unfamiliar wolves, and that includes all dogs. Wandering wolves can easily move more than 1,000 kilometers from where they were born.

In northern latitudes, wolves mainly prey on moose, roe deer and reindeer. They have no prejudice and will also eat any kind of domestic animal, including sheep, dog, cow or horse. An adult wolf can eat up to 8-9 kilos in a day. Its’ most well-known sound is the howl. A human ear will hear a wolf howl at up to ten kilometres distance. The wolf also has a bark, but otherwise, it is very quiet, except around its den, where it will frequently howl, together with its family, especially when leaving them, or coming back.

Swedish Carnivore Association’s comments

- There is room for many more wolves in Sweden. In 2020, Germany had 128 family groups of wolves, in a country considerably smaller and much more densely populated than Sweden. If they can, we can!

- We work against trophy/quota hunting and poaching of wolves.

- When wolves prey on domestic animals, we believe that protective hunting is acceptable, provided that other solutions first have been tried, such as predator-proof fencing and/or moving domestic animals indoors at night.

- The main large carnivore policy should be promoting co-existence. We humans need to learn how to best live side by side with our wildlife. This is also basic EU policy.

Image credits

From the top: 1-2 Staffan Widstrand, 3 Magnus Lundgren, 4-5 Staffan Widstrand, 6 Magnus Lundgren, 7 Staffan Widstrand

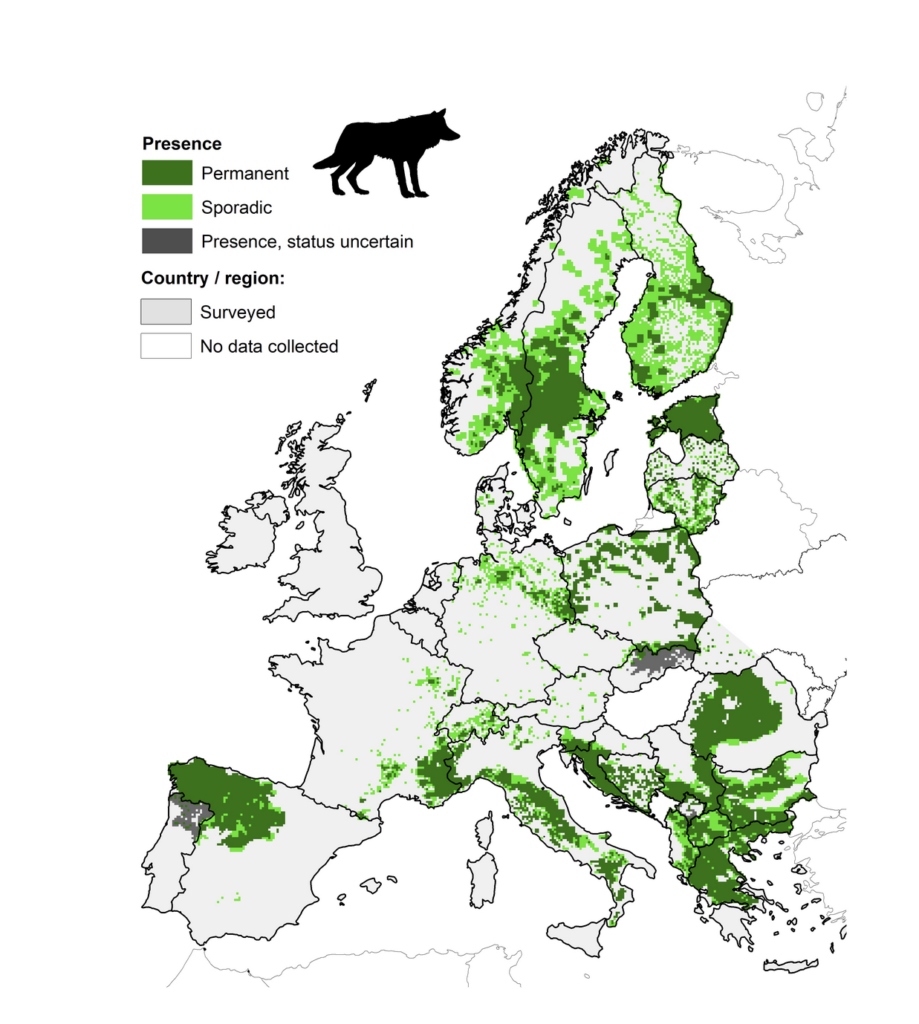

Map: Kaczensky, Petra et al. (2021). Distribution of large carnivores in Europe 2012 – 2016

Links

- Lowering the Protection status of the wolf? (European Environmental Bureau, EEB 2023)

- No evidence that public wolf hunting in Slovakia reduced livestock losses (Conbio, 2023)

- Understanding rural perspectives: A survey of attitudes towards large carnivores in rural communities (Eurogroupforanimals, 2023)

- Wolves contribute to disease control (Nature, 2019)

- Request for a consistent wolf management scheme in European Union (European Alliance for Wolf Conservation, 2017)

- Top predators constrain mesopredator distributions (Nature, 2017)

- Domestic animal losses and other damage by wildlife 2022 (Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SLU Viltskadecenter, 2023 Swedish)

- Commission proposes to change international status of wolves from ‘strictly protected' to ‘protected' based on new data on increased populations and impacts (EU Commission, 2023)

- European Study of Dog Bite Fatalities (Sciencedirect.org, 2020)

- Planned wolf cull endangers Swedish wolf population (Science, 2022)

- Wolves scare deer and reduce auto collisions 24% (AP News, 2021)

- The effectiveness of livestock protection measures against wolves (Elsevier, 2019)

- Distribution maps for Brown bear, Eurasian lynx, Grey wolf, and Wolverine [Dataset]. Kaczensky, Petra et al. (2021). Distribution of large carnivores in Europe 2012 - 2016: Dryad

News

What will the Wolf downgrade mean for Europe and Sweden?

- 12 May 2025

“Take Sweden’s wolf killing to the EU Court”

- 8 May 2025

53 Associations Call to Halt EU Wolf Downlisting

- 18 April 2025

87 lynx to be killed in Sweden

- 26 February 2025

Sweden's illegal wolf hunt starts on January 2

- 29 December 2024

Sweden’s wolf population to be cut by more than half

- 8 November 2024