Eurasian lynx

100 years of lynx conservation progress in Sweden is right now being undone at an alarming speed. Mainly because of high trophy hunting quotas, permitted by the Swedish government. This is not compatible to the lynx’ status as a protected species, neither in Sweden nor in the EU.

Why now?

In Sweden, an extensive, licensed trophy hunt for lynx is carried out annualy, in order to satisfy certain special-interest groups and officially to “increase acceptance” for the lynx, by shooting them. A hunt that is clearly against EU law. In 2023, this licensed hunt meant the killing of around 13% of the country’s lynx. This licensed hunt, together with the added so-called protective hunt, led to at least 218 wild lynx being killed, out of an officially estimated population of 1,417 individuals.

Government policy today aims at bringing down Sweden’s lynx population even further, seemingly trying to come as close as possible to the absolute minimum, the so-called “Favorable reference population” level, making this become the future ambition level for the lynx numbers. A level today defined by the Swedish authorities as 870 lynx.

Why should lynx be as few as possible in Sweden? Why not as many as possible? The way the lynx population survey statistics are presented has also been seriously questioned, since the official numbers easily give the impression that there are many more lynx than there actually are at the lowest. The annual survey count ends right before the massive legal hunting is carried out in March. So, in effect, the published official number each year is counted right before hundreds of lynx are killed in the hunt. On top of that, the numbers counted during the survey from October to February also include all lynx that have been found dead during the period, not deducting them from the reported total.

According to official statistics, 188 lynx were killed during “licensed quota hunting” in 2023. The same year, a further 30 were killed during “protective hunting”. Another 54 were found dead from natural reasons or road traffic. On top of those numbers, there are lynx that die from poaching (estimated by scientists in 1999 at c.100 – 150 per year) and lynx that die from natural causes, but are never found.

The result is that at the end of March there is every year far fewer lynx in Sweden, than the official estimate for that winter indicates. A more realistic lynx population number, measured at its lowest point in 2023, would then have been around 1,000 lynx. Which is very near the above mentioned minimum “Favorable reference population” level of 870 lynx.

Lynx conservation

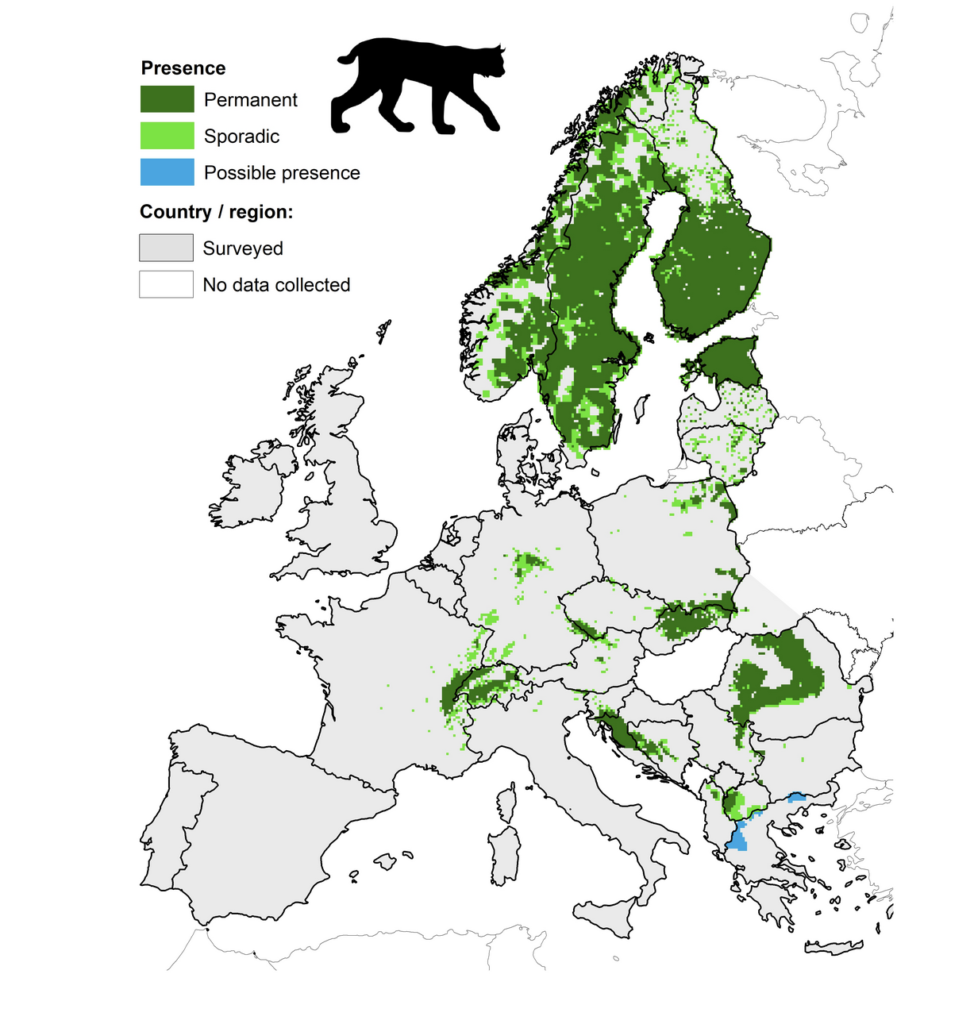

About half of Europe’s lynx are found in the Nordic countries. Therefore, Sweden’s lynx are vitally important for the total European lynx population. Official numbers in the winter 2022-2023 were estimated at 1,417 lynx in Sweden (right before the massive hunt).

Hunting is, since long, the main limiting factor for Sweden’s lynx. The lynx is very sensitive to high hunting pressure. Poaching is of course a serious problem and a crime, but today it is the “licensed quota hunting” that is the most problematic for lynx in Sweden. Especially when combined with the generous issuing of “protective hunting” permits. Quotas are justified by the authorities in order to actively reduce the number of lynx, in spite of the lynx being Strictly protected, through the EU Habitats Directive. According to the EU, depressing of a population (or quota hunting) is not compatible with the directive. However, this is exactly what is happening in Sweden right now. Special interest groups are trying to push up the hunting quotas for all large carnivores, including lynx, so that their population numbers are being brought down to soon critically low levels.

Very few Swedes have ever seen a lynx in the wild, and even fewer have ever had any problems with this almost invisible cat. It could be seen, at least by the non-hunting humans in Sweden, as difficult to justify such high hunting quotas for an animal that is Strictly protected in the EU. Finland, a smaller country than Sweden, still officially has twice as many lynx as Sweden does. On top of that, the Finns in their survey only count adult animals.

The lynx has been a protected species in Sweden, off and on since 1928, and more lately since 1991. It is also protected in all EU member states. The lynx is included in the Bern Convention, and in the EU Habitats Directive as a Strictly protected species. It is classified as “Vulnerable (VU)” by the Swedish “Red list” 2020, published by SLU Swedish Species Information Centre (SLU Artdatabanken) at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

Why does the ecosystem need the lynx?

The lynx has been an integral part of all land ecosystems in Sweden since before the last ice age, and returned up here as soon as the ice receded. Top predators are engines that drive evolution, by regulating the population sizes and behaviour of their prey, thereby being part of shaping nature around them. The lynx contributes to keeping the genetics of its prey healthy. Lynx also limit the numbers of smaller predators like the fox, which then influences all the fox’s prey species. In the mountains of the north, the lynx is a key provider of carrion for wildlife such as the arctic fox, wolverine, bear and birds. In the south, for the badger, fox and a variety of birdlife.

Why are lynx hunted in Sweden?

Basically, it comes down to competition between carnivores. There are two official ways to hunt lynx: Protective hunting “to protect property”, and licensed quota hunting, “to increase acceptance” and bring down lynx numbers. Most lynx are killed by hunters letting their gun dogs chase the lynx up a tree, in which the lynx is then shot. Or by tracking and encircling the lynx by a team of hunters and then often using dogs to flush the lynx to move. Even today, some lynx are still killed by trapping them in box live traps, where they are finally shot with a gun.

Protective hunting is officially allowed when lynx might kill domestic livestock, especially reindeer and sometimes sheep. In 2022, 120 out of Sweden’s then 342,000 sheep were killed or wounded by lynx, compared with the 228,860 sheep killed by humans that same year. Farms in lynx areas are recommended to try to prevent predator attacks, first of all by putting up predator-proof electric fences or using guard dogs. Livestock losses are much more likely in farms that have not yet taken preventive countermeasures. Electric fences tend to limit the problems with lynx predation on sheep. They also tend to keep the sheep in, and the neighbour’s dogs out. At a national scale, sheep losses caused by lynx is a minor problem, but for the individual farmer it can of course be a great loss. Any such loss is compensated for economically by the government.

Protective hunting is sometimes expanded into preventive measures, which is most common in the reindeer herding areas of the North. Here, lynx cause sizeable economic damage for reindeer owners. According to the Sami Council (Sametinget) in 2024, lynx kill between “10,000 to 50,000 reindeer” per year, out of about 250,000 reindeer in the country. Some Sami communities report reindeer losses to lynx of 30 to 40%. At a national scale, lynx predation on reindeer is a sizeable cost for the state, and represents 4 to 5 Million euro per year in damage compensation payments, plus the losses for the community of herdsmen.

Licensed hunting of lynx is officially done to “increase acceptance” by reducing the lynx population size. A lynx hunting quota is set each year, where every step in the decision making process is heavily influenced by hunting interests. In reality, this quota hunting is carried out because of two reasons. First, because the lynx is seen as a competitor of prey such as roe deer, that hunters want to keep their right to kill. Second, because of a certain demand for trophy and pleasure hunting. According to EU Habitat Directives, neither counts as a valid reason to allow a legal hunt of a strictly protected animal. The Swedish authorities that issue hunting quotas (based on the Government’s intentions) have therefore been taken to court several times in Sweden, and since March 15, 2024, there is now also a formal complaint lodged to the EU Commission, about the Swedish lynx hunting, filed by the Swedish Carnivore Association.

Are lynx dangerous to people?

There is not a single recorded case of an unprovoked attack by a lynx on a human in the wild. A few gun dogs get hurt or killed by lynx per year, most often in self-defence, when dogs have given chase. The odd hunter has also been hurt, when trying to save their dog.

Lynx facts

Latin: Lynx lynx

Swedish: Lodjur

The Lynx is the largest wild cat species in Europe. It has a spotted reddish-brown coat in the summer, greyish in the winter. Black ear tufts, a bobbed, black-tipped tail and its hind legs longer than the front legs. They are today found in all land-based ecosystems in Sweden, as long as there is food and they are not hunted too hard. Lynx prefer wooded terrain and they have extraordinary vision, hearing and sense of smell. Their favorite prey in southern Sweden is roe deer, and in the north, reindeer. Lynx also take hares, game birds and rodents, as well as smaller predators such as fox. Lynx generally don’t eat carrion.

During the mating season in March, lynx utter powerful shrieks at night. Adult lynx live alone, except females that have cubs. The normally 2-3 cubs are born in May or June and then stay with their mother for about a year.

The lynx is a strong symbol for Sweden’s natural heritage and for healthy ecosystems. Culturally, the lynx has always been one of the spiritual icons in Sweden’s forested lands and a part of our cultural heritage, myths, stories and art. The International Lynx Day is celebrated on June 11.

Swedish Carnivore Association’s comments

- Our ecosystems would do well with a much larger lynx population than today. There should be no quota hunting of lynx, nor of any other strictly protected predator.

- When lynx prey on domestic animals, we believe that protective hunting is acceptable, provided that other solutions first have been tried, such as predator-proof fencing and/or moving domestic animals indoors at night.

- Lynx survival in Sweden is not just a national issue, it is a European issue, since a significant part of Europe’s lynx are found here.

- We also prefer the catching and reintroduction of lynx to other countries, compared to just shooting them. Lynx have lately been reintroduced to Switzerland, Slovenia, Croatia, France, Italy, Czechia, Germany, Poland and Austria.

Image credits

From the top: 1-2 Staffan Widstrand, 3-4 Zdenek Machacek, 5 Staffan Widstrand, 6-7 Rolf Nyström

Map: Kaczensky, Petra et al. (2021). Distribution of large carnivores in Europe 2012 – 2016

Links

- Sweden hesitates to protect lynx against hunting (M. Apelblat, The Brussels Times, 12 Oct 2023)

- Final report – The Lynx project (Henrik Andrén & Olof Liberg, Grimsö research station, Department of Ecology, SLU, 2008, Swedish)

- Return of the missing lynx (Rewilding Europe, 2024)

- Nature and biodiversity, The Habitats Directive - Large carnivores (EU Comission webpage, 2024)

- Living side by side (Sweden’s Big Five, 2024)

- Distribution maps for Brown bear, Eurasian lynx, Grey wolf, and Wolverine [Dataset]. Kaczensky, Petra et al. (2021). Distribution of large carnivores in Europe 2012 - 2016: Dryad

News

Sweden launches hunt of protected wolverines

- 1 October 2024

Sweden to kill 20% of its brown bears

- 19 August 2024

Sweden aims at halving its wolf population

- 24 June 2024

Sweden's Wolves down by nearly 20%

- 3 June 2024

New carnivore protection project in Sweden

- 8 May 2024

Report dissuades from having 170 as the minimum number of wolves in Scandinavia

- 9 April 2024