Wolverine

A large share of Europe’s wolverines live in Sweden. Therefore, Sweden has a special responsibility to protect the wolverine and its habitats. However, in 2023 for the first time a licensed quota hunt of 15 wolverines took place. In spite of the wolverine being a protected species in Sweden and the EU, and in spite of its numbers being estimated at just barely reaching “Favourable Conservation Status”.

Why now?

Sweden’s government decided to allow for the hunting of wolverine again in 2022. The fact that the wolverine is a protected species in Sweden and the EU was not stopping them. Hunting is, since long, the main limiting factor for Sweden’s wolverine population. Illegal hunting, poaching, is a problem and a crime of course, but the “licensed quota hunting” in combination with generous “protective hunting” quotas, is even more problematic for the wolverine population. The official reason for allowing licensed quota hunting is to “regulate the number of wolverines to prevent damage to domestic animals and reindeer”.

Sweden is the 5th largest country in Europe, 450,000 Square kilometers in size and the latest survey shows that here live between 572 to 891 wolverines (The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency). For the wolverine to carry out its ecological role, there needs to be a certain number of wolverines. They are already too few. It is concerning that the wolverine in Scandinavia is among the mammals with the lowest genetic diversity of any examined, red-listed mammal.

Wolverine conservation

Wolverines have historically lived throughout Sweden’s northern boreal forests, mainly north of Stockholm region, according to centuries of hunting records and taxation statistics. The wolverine was hunted everywhere for its valuable fur and slowly pushed back until it only survived in the northernmost high-mountain areas. 1969 it was protected in Sweden. Since then, the Swedish wolverine population has slowly recovered. Despite its protection, the wolverine has been subject to both legal protective hunting and a certain degree of poaching. From 2022 the Licensed quota hunting was allowed, mainly in the reindeer herding areas in northern Sweden. To limit the costly losses of domestic reindeer, a management ambition has been to limit wolverine numbers in the north, and instead support the spread of the wolverine into the boreal forest lowlands in the south and east. This has been happening over the last 20 years.

In Sweden, wolverines are surveyed by the County Administrative Board’s staff, in cooperation with the Sami communities and on behalf of the Environmental Protection Agency. In 2023 there was an estimated 652 to 742 wolverines found throughout the northern mountains and down south towards Stockholm. It is a very fragile population, since the number of wolverines just barely meets the limit for what is considered minimum “Favourable conservation status” (600 individuals). They also suffer from very low genetic diversity.

The wolverine is Strictly protected in the Bern Convention, Category 2, and classified as “Vulnerable, (VU)” in the Swedish Red List, published by Swedish Species Information Centre (SLU Artdatabanken) at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. The species is protected according to the EU’s Species and Habitats Directive.

Why does the ecosystem need the wolverine?

Together with the other large predators, wolverines contribute to biological diversity and well-functioning ecosystems. It has lived here since the Ice age, and has an important role as a scavenger that tends to follow other predators such as lynx, bear, wolf and humans, at a distance. They are a part of an opportunistic clean-up squad that finishes what others have left behind. Their behavior helps to avoid freshwater contamination from rotting carcasses, limiting the possible spread of disease. Also, leftovers from the humans’ moose hunting teams or from reindeer slaughter sites, on the tundra and in the forest, are important parts of the wolverine’s diet.

Why are wolverines hunted in Sweden?

Basically, it comes down to competition between carnivores. There are two official reasons to hunt wolverine: protective hunting “to protect property” (mainly reindeer), and licensed quota hunting, “to limit damage” and regionally bring down wolverine numbers.

Between October 1 and December 31 in 2023 a licensed hunt for wolverines took place for the first time in decades and the quota was set to maximum 15 wolverines. The official reason for the licensed hunting in this case was to limit damages that wolverines cause to the reindeer husbandry. In 2023, local county administrations were allowed to decide on licensed hunting quotas for wolverine, after the Environmental Protection Agency, delegated the decision making power to their level. The main concern is as always around the domestic reindeer breeding herds in the mountain and forest areas of the North. In other parts of the country, the wolverine causes minimal damage to domestic animals.

Are wolverines dangerous to people?

No. There are no reports of people ever being attacked or injured by wild wolverines. If a human gets too close to a wolverine den with cubs, the female often leaves the cubs, and returns later, as soon as the danger is over. The wolverine has a false reputation in Sweden of being aggressive, when truth is rather the opposite. Shy and wary, like most scavengers eating carrion from larger predators that might be around. The myth about its grotesque volume-eating habits, might come from the fact that a wolverine can dismember and hide the remains of an entire reindeer or moose, overnight, in a relatively short time.

Wolverine facts

Latin: Gulo gulo (Linnaeus 1758)

Swedish: Järv

The wolverine is Europe’s largest marten. It is a predator with a small head and large paws. The wolverine resembles a short-legged bear, but moves more like a badger. Within the EU, the wolverine is only found in Sweden and Finland, while globally it exists all across the boreal forest and tundra belts in the Northern hemisphere. Wolverines are hunters, but more importantly scavengers, that tidy up left-overs from other large carnivores hunting success, mainly from humans, wolves and lynx.

Cubs are born in February or March and come out of the den with their mother at the end of April or early May. If there suddenly is a lot of food around, wolverines are very skilled at storing excess meat in rock cavities, tree tops and in snowdrifts. The wolverine is an opportunistic hunter that catches anything that it can come over, including hares, foxes, game birds and frogs. In the North the wolverine’s main prey is reindeer. Most of the year reindeer can outrun them, but during two seasons the reindeer are especially vulnerable to predation. It is when their calves are very young. Or when there is deep snow with weak crust. This enables a wolverine, on its snowshoe-like paws, to catch reindeer that get their legs bogged down in the snow. In these cases a single wolverine may kill several reindeer in a night. A reason why reindeer herders don’t like to have wolverines around.

In a Swedish field research site, in Northern Lapland, wolverines equipped with radio collars killed on average two reindeer a month. Wolverines in the boreal zone prey mainly on mountain hares, and small rodents when these have population peaks. Rodent numbers strongly influence the number and survival of wolverine cubs in Scandinavia.

Swedish Carnivore Association’s comments

- A significant part of Europe’s wolverines live in Sweden. That means that Sweden has a special responsibility for the survival and long term viability of the species and its habitats.

- Wolverines in Scandinavia are among the mammals with the lowest genetic diversity of any examined, red-listed mammal. This is a threat to the species’ long-term survival and we need wolverines to be able to immigrate from the Finnish/Russian wolverine populations.

- We work against annual licensed hunting quotas for any strictly protected predator. Once wolverine individuals do cause problems, we believe protective hunting may be an acceptable last resort, as long as other options have first been tried (in line with the EU Court’s decision Tapiola).

Image credits

From the top: 1 Günter Lenhardt, 2 Staffan Widstrand, 3-5 Magnus Lundgren

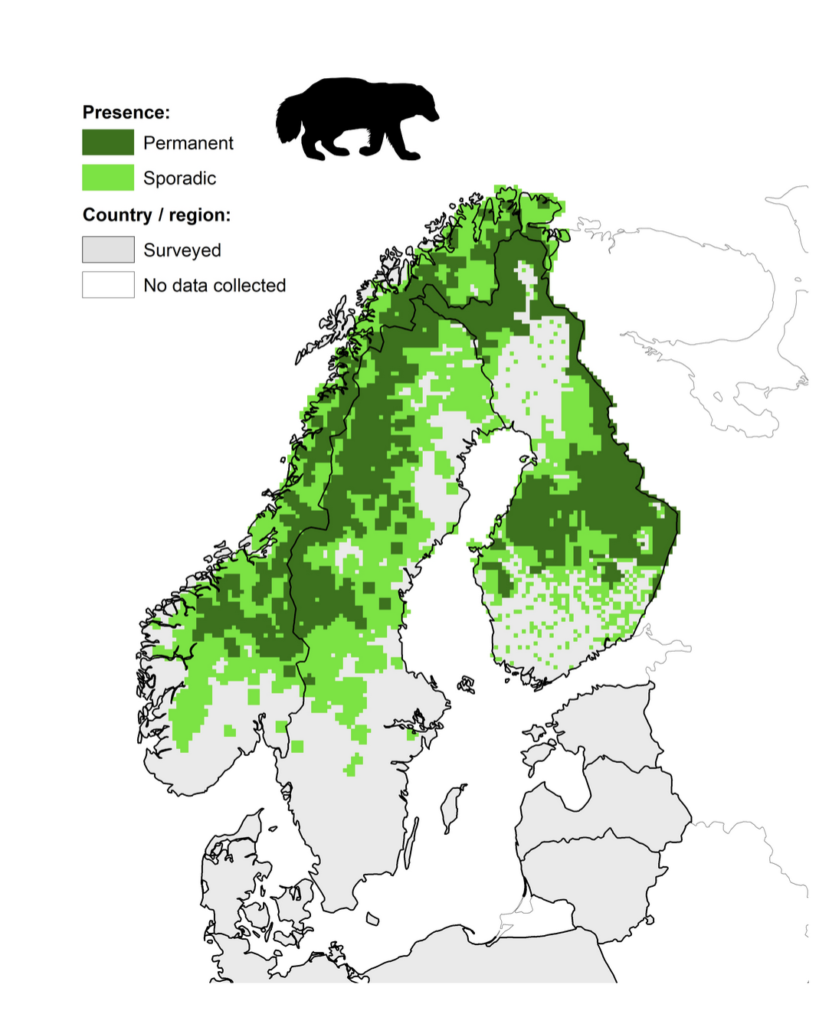

Map: Kaczensky, Petra et al. (2021). Distribution of large carnivores in Europe 2012 – 2016

Links

- Wolverine population (The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency)

- Wolverine’s low genetic variation (Uppsala University)

- Genetic diversity was among the lowest detected in a red-listed population (Uppsala University)

- Framework for Transboundary Cooperation on Management and Conservation of Wolverines in Fennoscandia (About Bern Convention)

- Distribution maps for Brown bear, Eurasian lynx, Grey wolf, and Wolverine [Dataset]. Kaczensky, Petra et al. (2021). Distribution of large carnivores in Europe 2012 - 2016: Dryad

News

Hundreds of millions wasted on culling wolf population

- 8 October 2025

Podcast well worth listening to

- 19 September 2025

250,000 Swedish kronor reward for tips on illegal hunting of large predators

- 10 September 2025

124 swedish bears shot on the first day of hunting

- 21 August 2025

Sweden prepares for another major bear hunt

- 4 August 2025

EU Court ruling confirm flaws in Sweden’s wolf policy

- 11 July 2025